Yang Chengfu, grandson of Yang Luchan—the founder of Yang-style Taichi—was instrumental in popularizing the art across China. In the 1920s and 1930s, he traveled extensively, teaching in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing, and Guangzhou. His efforts introduced Yang-style Taichi to a broader audience or its benefits for health, martial arts, and personal development.

While his ancestors contributed immensely to developing the Yang style, they left no written records or visual documentation for future generations. Yang Chengfu made significant contributions to the preservation and understanding of Taichi by documenting its principles and techniques. Though he did not personally write books, he dictated key theories and practices, which his students compiled into foundational texts. Additionally, Yang Chengfu published two sets of illustrated posture photographs, providing vivid visual references for each movement.

Among his most notable contributions were the Ten Essentials of Taijiquan, a set of guiding principles that emphasize proper posture, intention over force, and harmonious body coordination, which remain cornerstones of Taichi practice today.

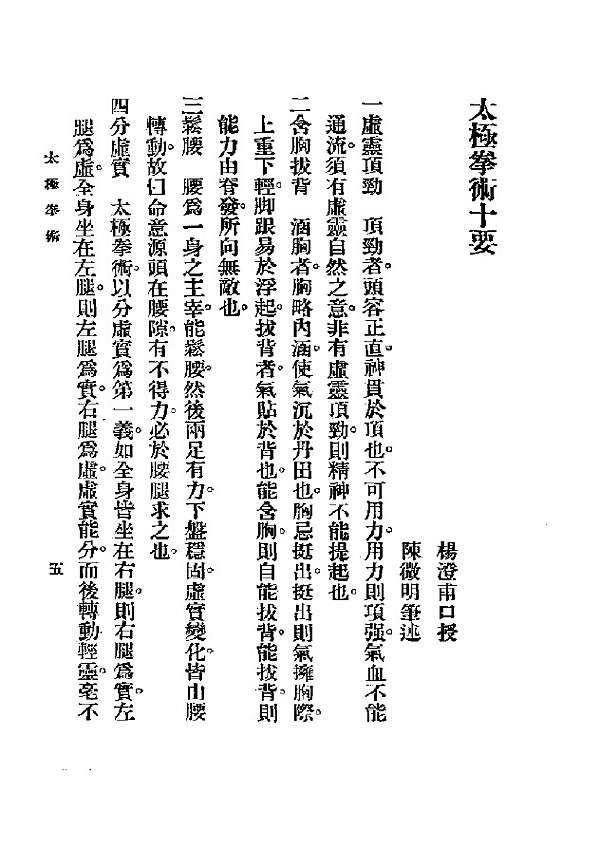

The original Chinese wording is shown below.

However, it was not an easy task to interpret into English. The approximate meanings are:

1. An Intangible Energy Lifts the Crown of the Head

This principle emphasizes maintaining an upright posture by imagining an invisible thread gently pulling the crown of your head upward. This subtle lift encourages relaxation throughout the body, elongates the spine, and promotes the smooth flow of energy (qi). Avoid tension—let the feeling be light and natural.

2. Contain the Chest and Round the Back

Rather than puffing out the chest, slightly sink it inward to allow the back to naturally round. This positioning fosters a stable center of gravity and enhances the connection between the upper and lower body. It’s a balance of openness and containment, creating a sense of internal harmony.

3. Loosen the Waist

The waist acts as the pivot of Taijiquan movements. Keeping it loose and flexible enables fluid transitions and ensures the power generated from the legs is effectively transferred through the body. A stiff waist disrupts this flow, making movements less coordinated.

4. Distinguish Yin and Yang

A cornerstone of Taijiquan, distinguishing yin (soft, yielding) and yang (hard, assertive) is essential to creating dynamic balance. Shifting weight clearly between your feet or alternating energy in movements reflects this principle. Understanding this interplay enhances your martial effectiveness and internal equilibrium.

5. Sink the Shoulders and Drop the Elbows

Tension in the shoulders and elbows disrupts the free flow of energy. Allow the shoulders to relax and the elbows to sink naturally, creating a smooth pathway for energy and preventing unnecessary stiffness in movements.

6. Use Intention, Not Physical Force Only

Taijiquan prioritizes the use of intention (yi) over brute strength. Direct your movements with focused awareness and mental clarity. This principle transforms Taijiquan into an internal art, where power arises from the mind-body connection rather than muscle strength alone.

7. Upper and Lower Follow One Another

Unity between the upper and lower body is fundamental in Taijiquan. Movements should flow seamlessly from the feet through the waist to the hands. This harmony ensures that power is generated and expressed as a unified whole.

8. Internal and External Are United

In Taijiquan, the inner state of mind and external physical movements are interconnected. Cultivate calmness and clarity within to guide the outward expression of forms. The unity of internal intent and external action creates grace and power.

9. Linked Without Breaks

Taijiquan movements are continuous and unbroken, like an endless thread. Transitions should be smooth, with no abrupt stops or gaps. This quality reflects the Taoist concept of flow and ensures the integrity of each form.

10. Seek Stillness in Motion

Even amidst motion, there is a stillness—a calm awareness that anchors the practitioner. This principle encourages mindfulness and presence, transforming Taijiquan into a moving meditation. Finding stillness within motion allows for deeper connection and balance.

The Ten Essentials of Taijiquan are more than technical guidelines; they are the heart of the practice. By embodying these principles, practitioners can deepen their understanding of Taijiquan’s philosophy and improve their physical execution.

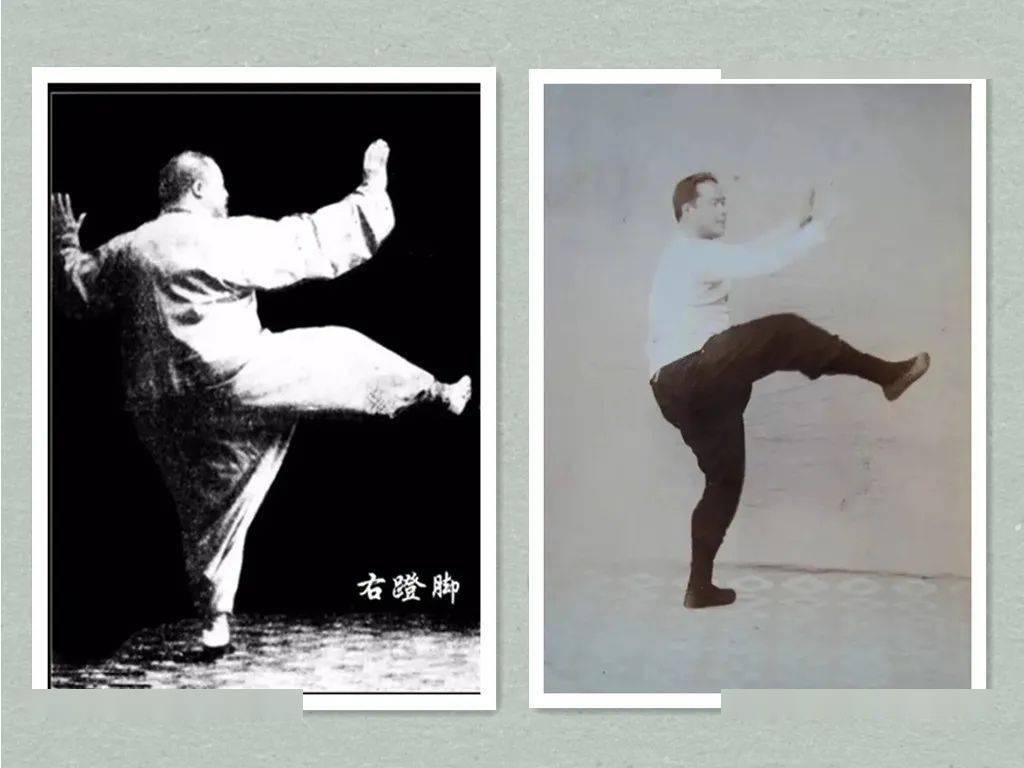

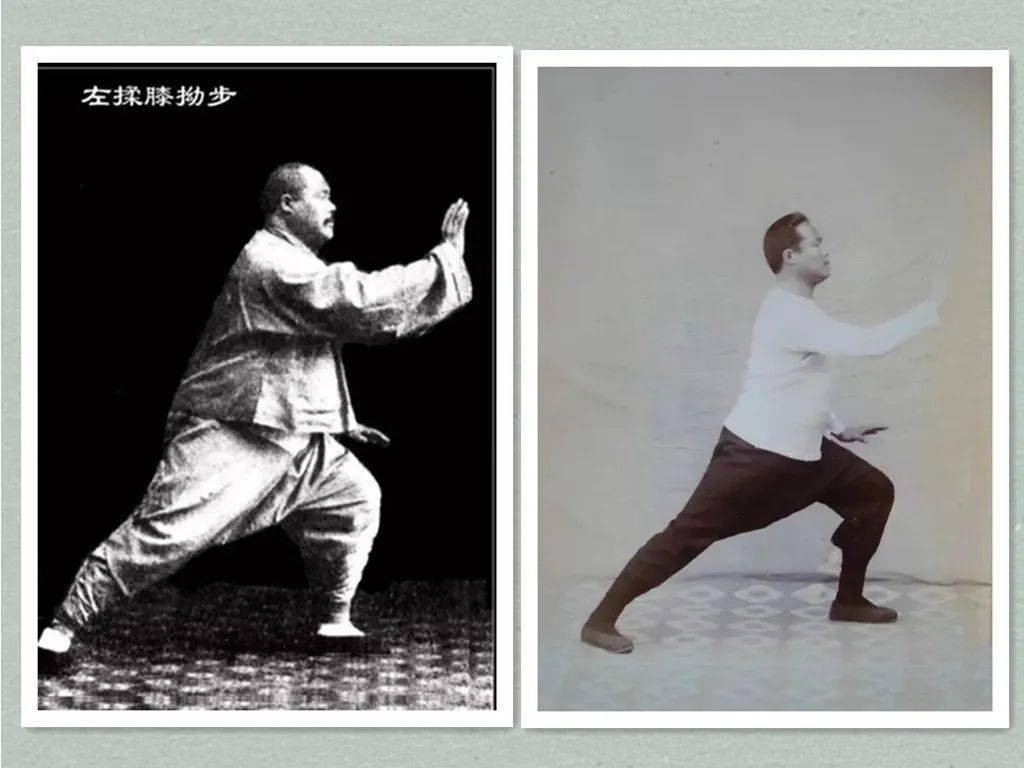

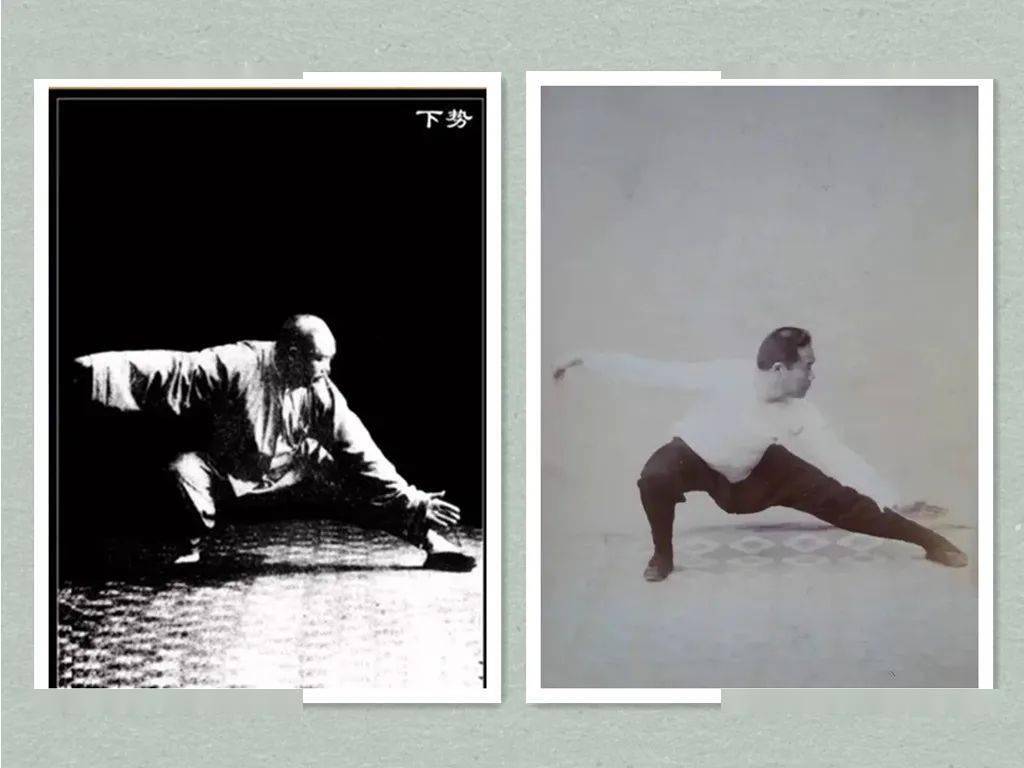

Yang Chengfu’s posture pictures, shared during our in-person class when each new movement is introduced, are invaluable in helping practitioners understand the essence of Tai Chi.

These images capture the nuances of alignment, transitions, and energy flow, serving as a clear guide to refining each form.

By linking these visual aids with the ten essentials, we gain a deeper understanding of how to implement them into our practice, ensuring the successful execution of every movement. The ten essentials need to be implemented into each Tai Chi movement. Whether you are a beginner or an advanced practitioner, revisiting these essentials can unlock new layers of growth and insight.